This votive crown, from the Treasure of Guarrazar, belonged to Recceswinth, the early medieval Visigoth King, who ruled from 649-672. Not designed for wear, but rather to hang as votive offerings, these crowns were typical of the Early Middle Ages, although pagan examples also exist. The phrase on the pendilia reads RECCESVINTUVS REX OFFERET, or 'King Recceswinth offered this.' Votive offerings, or deposits, were made for spiritual purposes, either as a thanks, a vow, or to invoke supernatural powers, thus could be anticipatory or ex postfacto; curse tablets, or defixios, were Graeco-Roman sheets made of tin or lead that wished misfortune upon someone, but gratitude was more typical, often including the more recognisable offerings of lit candles, statues, flowers, and jewellery.

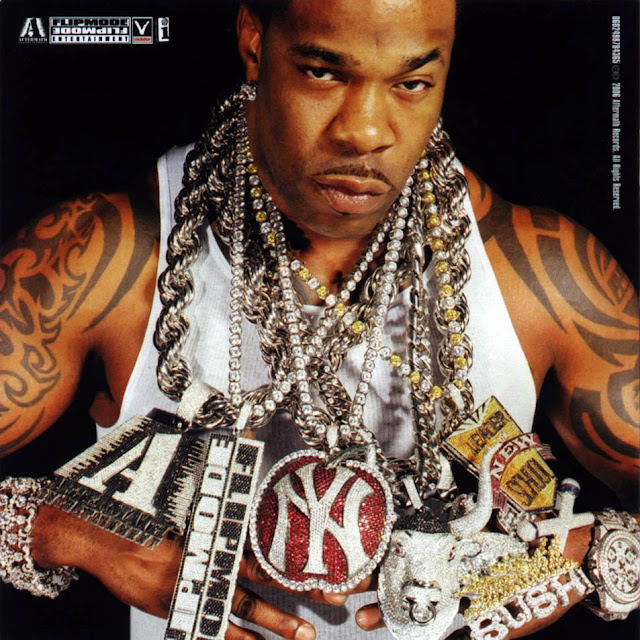

Which pretty much brings us up to speed. Logo jewellery and brandish charms are the modern tribute symbol par excellence, the simplest and most effective way to delineate your in-group out-group divide and identify with all that the symbol represents. Our example from over 1,300 years ago offered to God and required enormous amounts of wealth, whilst our modern day deposits, though requiring similar $$ contributions, seem to offer to no-one. Their prêt-à-porter symbols seem to be tributes to money itself, which negatively offer by way of presenting to others their exclusion from the club. This phenomenon is most interesting is its excess, which that holy subgenre of hip hop, gansta rap, displays with more ambiguity than Damien Hirst's diamond skull.

Whilst the popularity of Chanel, Tiffany, D&G, LV logos, wearable as charms, are relatively simple status symbols, For the Love of God, Hirst's memento mori is less so. Gangsta rap and hip hop branding, including the obvious irony of the Beastie Boys sporting a non-luxury brand VW logo, play with the same ambiguities, smile the same knowing smile. The irony is so inbuilt that it is hard to be either repulsed or admiring for long; a confused whirring between the two is the probably the most appropriate response to such an obvious play with symbolic meaning. Fittingly, the slang term playa usually refers to men who use minimal effort to get what they want from women, or to those who play the life game and come out on top; power, money, status. Recceswinth was, I'm sure, playing for similar rewards, only whose particulars have changed over the centuries. Don't hate the playa, hate the game? Perhaps. Exploiting the symbol to the point of crassness is at least more eye-opening than the banal toting of coy arm and throat candy.

_-_WGA17622.jpg)